Day three of our ascent of Kilimanjaro and we set off up a forbidding slope – rocky, steep, its surface uneven with gravel and boulders.

After an hour or so, I looked to see if our porters were still behind us. They carried our tents, our clothes, cooking equipment, food and drink… packages the size of a horse on their heads, while we had little knapsacks with sandwiches and a raincoat.

The porters were nowhere to be seen. “What’s happened to them?” I asked our guide Soster. “They took the short route,” he said.

Then I spotted these superhuman mountain goats with their vast loads springing up an ultra-steep path, forging ahead so that they could set up camp and cook dinner in time for our arrival.

We had eight staff – six porters plus two guides - catering to the two of us, certainly the highest ratio I’ve ever enjoyed.

Although climbing Kilimanjaro is a stroll compared with other continents’ highest peaks, it’s still a challenge. We took six days in total: four days up and two days down. You need to acclimatise gradually, or else risk altitude sickness. We did the Marangu route, where you ascend for a couple of days, dip down, then climb back up again.

Only around 65 per cent of Kilimanjaro climbers make the summit. We met a few along the route who had turned back, stricken by altitude sickness and exhaustion.

Altitude has unpredictable effects. For some (me included) it provokes irritability: I became so fed up with walking downhill, knowing that I’d have to go back up, that I started kicking random stones in frustration.

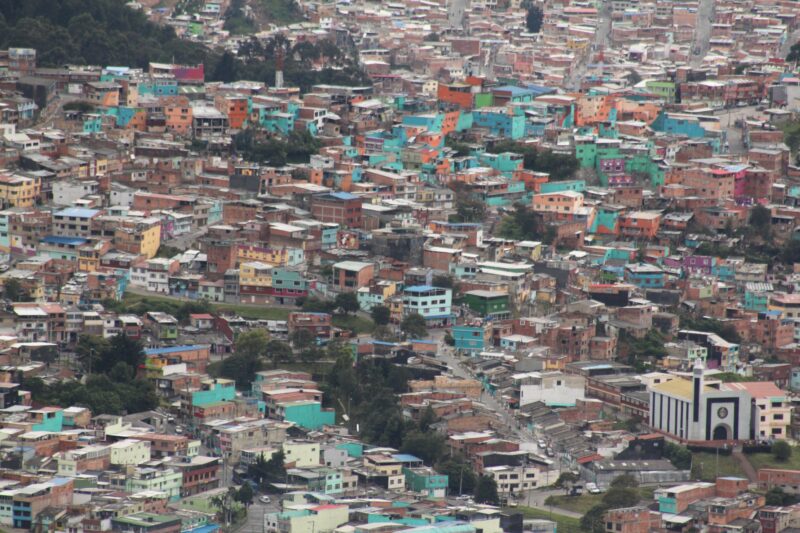

In compensation, the scenery was breath-taking, from savannah to glacier to tropical rainforest. The final ascent, begun at just after midnight so that you reach the summit in early morning, was unforgettable. You really get a sense of being wildly high, with a vast volcanic crater below and the whole of Africa spreading out in every direction.

It was an awesome adventure.